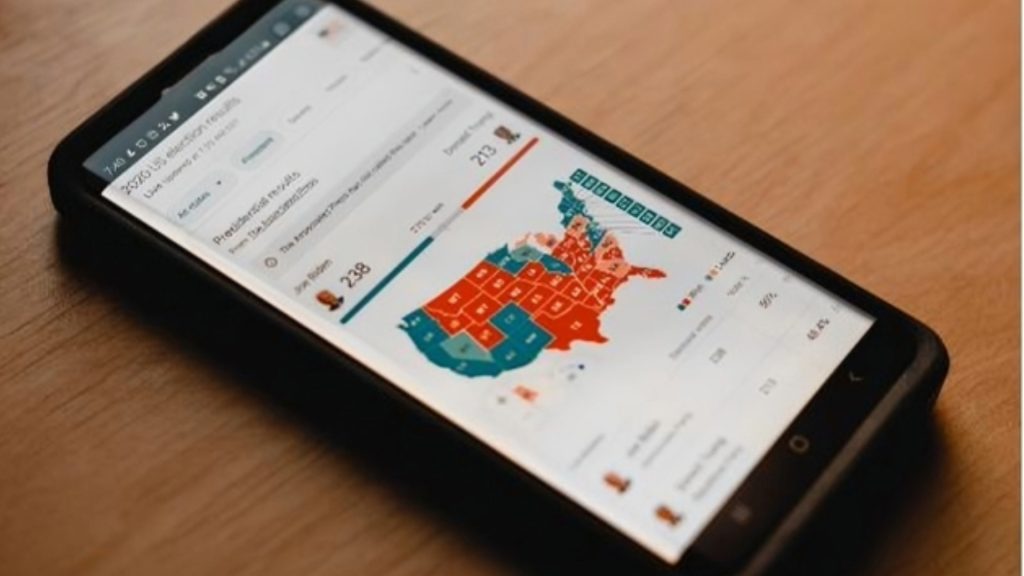

Political polarization in America has intensified in recent years. According to experts, the contemporary political scene is dominated by emotions and personal beliefs rather than policy preferences. This tendency to form tight-knit groups with those who share similar views while demonizing opposing groups is an evolutionary adaptation for human survival.

Political scientists have studied this trend of “affective polarization”, where people’s political stances are strongly tied to their emotions and feelings about others. Research shows over 50% of Republicans and Democrats now see the opposing party as a threat to the nation.

Historical Context of Political Fractiousness

The United States has grappled with political divisions since its founding, but recent decades have seen polarization intensify in new ways. As social scientists have noted, affective polarization based on emotions and group identity rather than policy differences alone now defines the political landscape.

According to researchers, this polarization stems in part from innate human tendencies to form in-groups and out-groups as a means of survival. However, the American political system also reinforces such divisions.

The Rise of Affective Polarization

Affective polarization refers to the tendency of individuals to dislike and distrust members of the opposing political party. According to political scientists like Lilliana Mason, affective polarization in the U.S. has been intensifying in recent decades.

There are several factors contributing to the rise of affective polarization. First, geographic sorting has resulted in greater physical separation of Democrats and Republicans. People are increasingly likely to live in neighborhoods and communities dominated by those with similar political beliefs.

Evolutionary Roots of Group Identification

Human beings have an innate tendency to form groups and identify with those groups. According to Nicholas Christakis, a Yale sociologist, “Homo sapiens is a social species; group affiliation is essential to our sense of self.” This inclination to bond with like-minded individuals and form tightly-knit collectives evolved as a survival mechanism, enabling cooperation and resource sharing.

However, the human predisposition for group formation also bred intergroup conflict and hostility. Defining a group necessitates distinguishing its members from outsiders, and this process of differentiation can foster feelings of contempt for those excluded from the group.

Lessons from the Warring Boy Scouts

Muzafer Sherif’s 1954 experiment provides insights into modern political divisions. Sherif separated 22 Boy Scouts into two groups at a summer camp. Initially, the groups were unaware of each other. After a week, the groups learned of the other’s existence and developed an irrational contempt, seeing the other group as “fundamentally flawed.”

Political parties today exhibit similar tendencies. They are defined in opposition to each other – to win is for the other to lose. Candidates who stoke resentment across divisions are often successful. Psychologist Shanto Iyengar notes that humans crave group affiliation, leading to an “us versus them” mentality.

Group Affiliation in Homo Sapiens

Humans are innately prone to identifying with groups. According to Shanto Iyengar, a Stanford political psychologist, “Homo sapiens is a social species; group affiliation is essential to our sense of self. Individuals instinctively think of themselves as representing broad socioeconomic and cultural categories rather than as distinctive packages of traits.”

The human desire to belong to a group has evolutionary roots, as cooperation and identifying rivals were necessary for survival. As Nicholas Christakis, a Yale sociologist, explains, “The evolution of cooperation required out-group hatred, which is really sad.” Even young children tend to prefer those assigned to the same arbitrary group.

Political System Dynamics

The American political system cultivates polarization through its winner-take-all dynamics and absence of power-sharing mechanisms. The country’s two-party system and lack of a parliamentary system mean that control of political power is scarce and intensely fought over.

Elections in the U.S. are typically zero-sum, with one party winning majorities and the other losing influence. This fosters an “us vs. them” mentality and the view that the other party’s gains equate to one’s losses. The redistricting of congressional districts into “safe” red or blue seats also reduces incentives for moderation and compromise.

Redistricting and Lack of Competitive Races

Redistricting has contributed to the polarization of American politics by limiting the number of competitive congressional races. Since the 1990s, the majority of congressional districts have been “safe seats” that strongly favor one party over the other.

The redistricting process, in which state legislatures redraw district boundaries every 10 years following the census, has enabled the political parties to gerrymander districts to their advantage. By reconfiguring district lines to concentrate voters of the opposing party in as few districts as possible, the controlling party in the legislature can maximize the number of districts their party is likely to win.

Technological Influence: The Sorting Phenomenon

The advent of new technologies has enabled people to curate their media consumption in a way that reinforces their preexisting beliefs. Shanto Iyengar refers to this phenomenon as “sorting.” As people select media sources and social networks that align with their ideological views, they isolate themselves in “echo chambers.”

Within these echo chambers, affective polarization intensifies. Exposure to opposing perspectives decreases, fueling more extreme views of the “out-group.” Research shows over 50% of Republicans and Democrats now see the opposing party as “a threat.” Nearly 30% agree the other party “behave[s] like animals.”

Intensification of Affective Polarization

Research shows that affective polarization is intensifying across the political spectrum. Recent surveys indicate that more than half of Republicans and Democrats view the opposing party as “a threat,” and nearly as many characterize the other party as “evil.”

Political psychologists have found that humans have an instinct to form tight-knit groups for survival and to identify adversaries who compete for resources. According to experts, the human tendency to categorize people into “us versus them” groups is an evolutionary adaptation.

Concerns Among Voters

Voters across the political spectrum have expressed apprehension over the growing divide between the two major parties in the United States. Many citizens feel confused and concerned by the policy positions and rhetoric espoused by the opposing party’s candidates and supporters.

A study by political scientists Shanto Iyengar and Sean Westwood found that over 50% of Republicans and Democrats view the opposing party as “a threat to the nation’s well-being.” Nearly as many agree with describing the other party as “evil.” Voters worry this level of antagonism and contempt will make bipartisan cooperation and compromise nearly impossible.

Trump’s Role in Political Polarization

Donald Trump’s rise and time in office has significantly contributed to the intensification of political polarization in America. His rhetoric and actions have exploited and aggravated existing divisions, cultivating a devoted base while provoking intense opposition.

Throughout his presidency, Trump employed inflammatory language and violated long-held political norms, referring to the media as “the enemy of the people” and promoting a vision of the nation under threat. His messages frequently stoked fear and anger in his supporters by portraying them as besieged by nefarious forces seeking to undermine their way of life.

Media’s Contribution to Polarization

The media landscape in the U.S. has fragmented significantly in recent decades, with the rise of cable news and social media. This fragmentation has enabled individuals to curate information that reinforces their preexisting beliefs and values in what scholars call “echo chambers.”

Partisan news outlets and social media platforms have exploited human tendencies to pay more attention to threatening or emotionally evocative information. As Iyengar notes, “We don’t turn our head really quickly to look at a beautiful flower. We turn our heads quickly to look at something that may be dangerous.”

Political Operatives and Divide-and-Conquer Politics

Political operatives and strategists have learned how to effectively exploit human tendencies towards tribalism and group identification for political gain. By framing issues and policies in an “us versus them” narrative, these operatives are able to tap into feelings of resentment and contempt for the opposition, intensifying divisions among the electorate.

Research shows that people naturally form groups and alliances, in part as an evolutionary survival mechanism to identify competitors for limited resources. However, defining groups inherently requires determining who is excluded, which can breed irrational animosity.

Trump’s Polarization Powers

Trump frames politics as an “us vs. them” conflict, promoting a vision of virtuous citizens under siege. At a recent New Hampshire rally, Trump stated, “They’re not after me, they’re after you. … And I’m just standing in the way!” This rhetoric casts his opponents as threatening enemies targeting ordinary Americans.

Trump’s former rival Vivek Ramaswamy told the crowd, “We are in the middle of a war in this country … between the permanent state and the everyday citizen.” By framing politics as an existential struggle, Trump activates a sense of threat that fuels sectarianism. His rhetoric violates norms of civility, using inflammatory language to stoke outrage and signal virtue to his base.

The Future of Polarized Politics

The political divide in America appears to be intensifying, with data indicating affective polarization is on the rise. As Mason notes, “more than half of Republicans and Democrats view the other party as a threat’, and nearly as many agree with the description of the other party as ‘evil’.”

As Iyengar argues, the two-party system fuels out-group antagonism by framing politics as a zero-sum game. Voters see their ideological opponents not just as rivals but as fundamentally misguided or even malicious. Compromise and cooperation become less likely when each side views the other with distrust or disdain.